Mauricio Paredes, a former political prisoner of Chile’s dictatorship, said entering the U.S. amid Trump administration crackdown is evidence that ‘the system works’

Director of Syracuse University’s Santiago Center Program, Mauricio Paredes, visited campus last week, connecting with prospective students and program alumni. During his visit, Paredes moderated an alumni-led panel “Empanadas and Santiago: Discover Study Abroad in Chile,” hosted a lunch for Spanish-speaking students and spoke on a panel titled “Lessons from the South: Dictatorships and Resilience in Latin America.”

As a former political prisoner of Chile’s Augusto Pinochet dictatorship, the U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act makes it difficult for Paredes to enter the United States, but he made the decision to come anyway this fall.

“To me it’s really good to see that the experience (abroad) was meaningful and has shaped a bit of who you all are today. That is super heartwarming for me,” Paredes said. In addition to wanting to see all of his former students, Paredes said he also didn’t want to cower to the Trump administration.

Amid the administration’s crackdown on immigration, Paredes was originally not planning on visiting Syracuse this term. Earlier this year, SU removed the part of his contract that requires Paredes come to campus once an academic year. Paredes launched the Syracuse Santiago program in 2008.

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act includes a clause that individuals with certain political histories or associations deemed a risk to U.S. foreign policy could be denied entry to the United States. While the Chilean government, under former president Patricio Aylwin, pardoned Paredes in the nineties, it is still difficult for him to enter the U.S., Paredes said. The United States played a role in launching a coup against then-president Salvador Allende, a democratically-elected socialist.

“To be in the U.S. is super meaningful to me because I should supposedly not be able to,” said Paredes, who has been granted a limited one-year visa for entry.

For alumni of the Santiago Center program, Paredes’ visit is equally as important. Santiago Center alumnus and Syracuse Abroad campus outreach specialist, Nico Perez, said it means everything to him to have Paredes here this week.

“As an underappreciated program we are always doing everything we can to uplift the Santiago Center, and students being able to meet (Paredes) in person does a lot to boost engagement and excitement,” Perez said.

As Syracuse Abroad’s only center location outside of Europe, enrollment for the Santiago Center program trails behind locations such as Madrid and Florence. Enrollment in the Santiago Center typically ranges from 10-20 students, while the Florence Center has nearly 400 students attending this fall, Perez said. But students attest to the Santiago program’s value, highlighting travel opportunities and immersive educational opportunities as draws of the program.

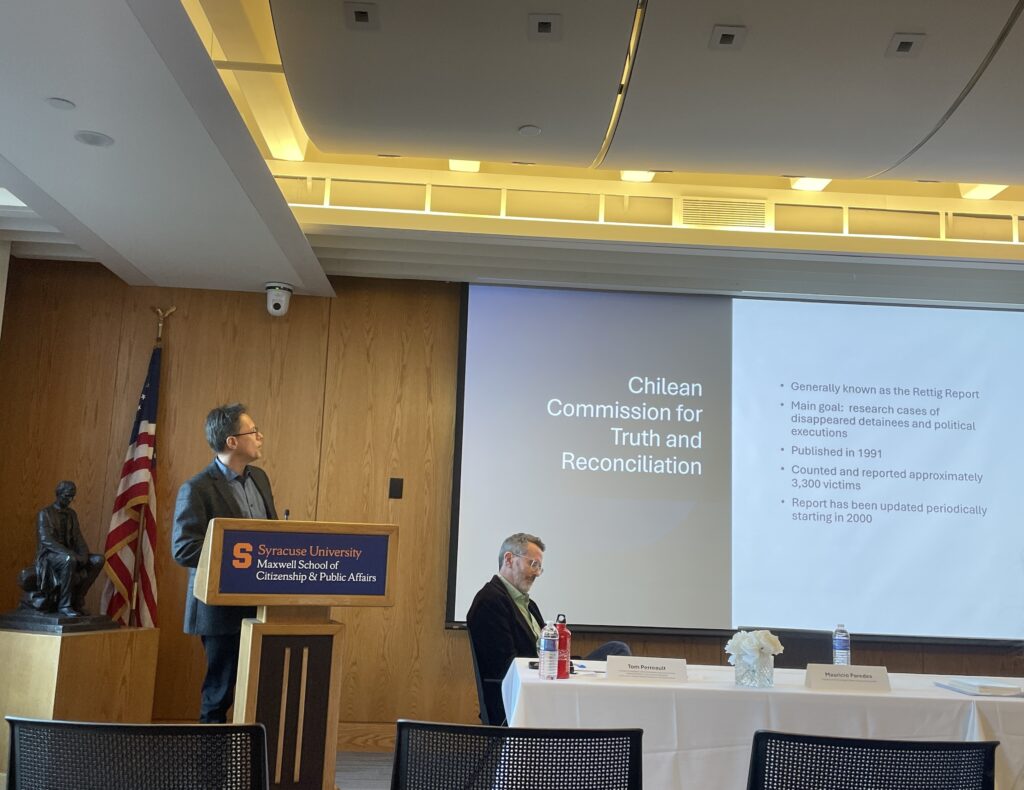

During the Tuesday panel discussion “Lessons from the South” Paredes alluded to these educational opportunities, describing his own research into the Chilean dictatorship and how he covers it in his course “Human rights, dictatorships, and historical memory.”

At the end of the panel Paredes was bombarded by students and colleagues alike who wanted to say their final goodbyes or hear more of his expertise. While the panel discussion delved into the prevalence of authoritarian regimes and trends in Latin America, Paredes viewed his ability to be in Syracuse this week as a sign of progress.

“What it really means to be here is that the system works. It gives me faith in democracy, in people, and in the system,” Paredes said.